Reviews

5 Significant Object Detection Challenges and Solutions

The field of computer vision has experienced substantial progress recently owing largely to advances in deep learning, specifically convolutional neural nets (CNNs). Image classification, where a computer classifies or assigns labels to an image based on its content, can often see great results simply by leveraging pre-trained neural nets and fine-tuning the last few throughput layers.

Classifying and finding an unknown number of individual objects within an image, however, was considered an extremely difficult problem only a few years ago. This task, called object detection, is now feasible and has even been productized by companies like Google and IBM. But all of this progress wasn’t easy! Object detection presents many substantial challenges beyond what is required for image classification. After a brief introduction to the topic, let’s take a deep dive into several of the interesting obstacles these problems face along with various emerging solutions.

Introduction

The ultimate purpose of object detection is to locate important items, draw rectangular bounding boxes around them, and determine the class of each item discovered. Applications of object detection arise in many different fields including detecting pedestrians for self-driving cars, monitoring agricultural crops, and even real-time ball tracking for sports. Researchers have dedicated a substantial amount of work towards this goal over the years: from Viola and Jones’s facial detection algorithm published in 2001 to RetinaNet, a fast, highly accurate one-state detection framework released in 2017. The introduction of CNNs marks a pivotal moment in object detection history, as nearly all modern systems use CNNs in some form. That said, the remainder of this post will focus on deep learning solutions for object detection, though similar challenges confront other approaches as well. To learn more about the basics of object detection, check out my post on the Metis blog: “A Beginner’s Guide to Object Detection.”

Challenges

1. Dual priorities: object classification and localization

The first major complication of object detection is its added goal: not only do we want to classify image objects but also to determine the objects’ positions, generally referred to as the object localization task. To address this issue, researchers most often use a multi-task loss function to penalize both misclassifications and localization errors.

Regional-based CNNs represent one popular class of object detection frameworks. These methods consist of the generation of region proposals where objects are likely to be located followed by CNN processing to classify and further refine object locations. Ross Girshick et al. developed Fast R-CNN to improve upon their initial results with R-CNN. As its name implies, Fast R-CNN provides a dramatic speed-up, but accuracy also improves because the classification and localization tasks are optimized using one unified multi-task loss function. Each candidate region that may contain an object is compared to the image’s true objects. Candidate regions then incur penalties for both false classifications and misalignment of the bounding boxes. Hence, the loss function consists of two kinds of terms:

\[\mathcal{L}(p, u, t^u, v) = \overbrace{\mathcal{L}_c(p,u)}^{classification} + \lambda\overbrace{\left[u\geq 1\right] \mathcal{L}_l(t^u, v)}^{localization}, \]

where the classification term imposes log loss on the predicted probability of the true object class \(u\) and the localization term is a smooth \(L_1\) loss for the four positional components that define the rectangle. Note that the localization penalty does not apply to the background class when no object is present, \(u=0\). Also note the parameter \(\lambda\) may be adjusted to prioritize either classification or localization more strongly.

2. Speed for real-time detection

Object detection algorithms need to not only accurately classify and localize important objects, they also need to be incredibly fast at prediction time to meet the real-time demands of video processing. Several key enhancements over the years have boosted the speed of these algorithms, improving test time from the 0.02 frames per second (fps) of R-CNN to the impressive 155 fps of Fast YOLO.

Fast R-CNN and Faster R-CNN aim to speed up the original R-CNN approach. R-CNN uses selective search to generate 2,000 candidate regions of interest (RoIs) and passes each RoI through a CNN base individually, which causes a massive bottleneck since the CNN processing is quite slow. Fast R-CNN instead sends the entire image through the CNN base just once and then matches the RoIs created with selective search to the CNN feature map, yielding a 20-fold reduction in processing time. While Fast R-CNN is much speedier than R-CNN, yet another speed barrier persists. It takes approximately 2.3 seconds for Fast R-CNN to perform object detection on a single image, and selective search accounts for a full 2 seconds of that time! Faster R-CNN replaces selective search with a separate sub-neural network to generate RoIs, creating another 10x speed up and thus testing at a rate of about 7-18 fps.

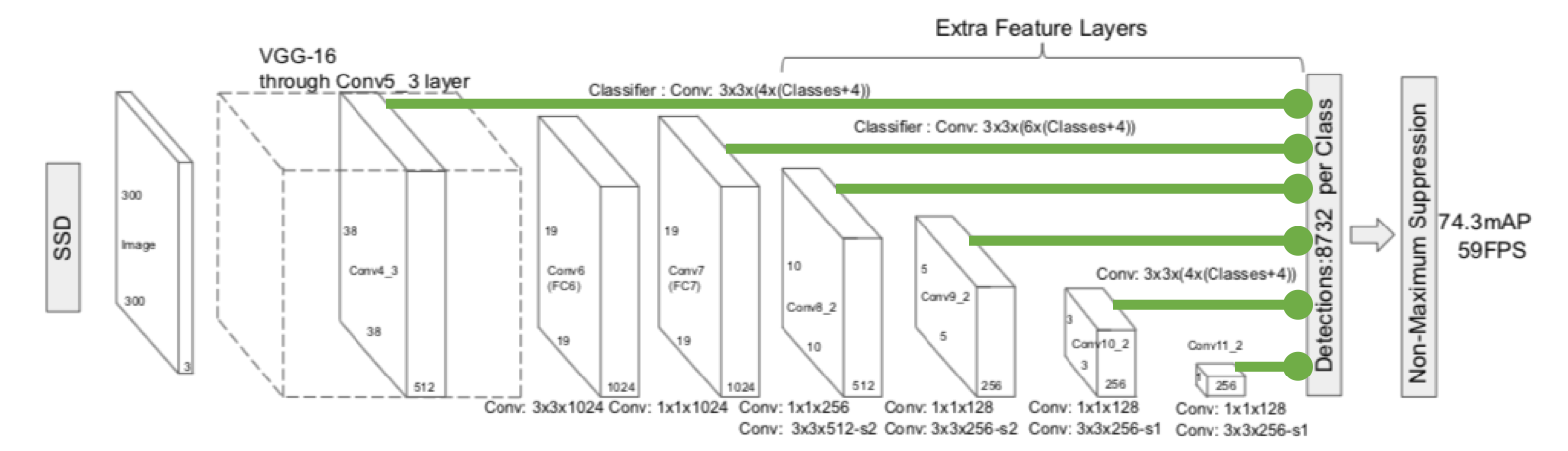

Despite these impressive improvements, videos are typically shot at at least 24 fps, meaning Faster R-CNN will likely not keep pace. Regional-based methods consist of two separate phases: proposing regions and processing them. This task separation proves to be somewhat inefficient. Another major type of object detection systems relies on a unified one-state approach instead. These so-called single-shot detectors fully locate and classify objects during a single pass over the image, which substantially decreases test time. One such single-shot detector YOLO begins by laying out a grid over the image and allows each grid cell to detect a fixed number of objects of varying sizes. For each true object present in the image, the grid cell associated with the object’s center is responsible for predicting this object. A complex, multi-term loss function then ensures that all localization and classification occurs within one process. One version of this method, Fast YOLO, has even achieved rates of 155 fps; however, classification and localization accuracy drops off sharply at this elevated speed.

Ultimately, today’s object detection algorithms attempt to strike a balance between speed and accuracy. Several design choices beyond the detection framework influence these outcomes. For example, YOLOv3 allows images of varying resolution: high-res images typically see better accuracy but slower processing times and vice versa for low-res images. The choice of the CNN base also affects the speed-accuracy tradeoff. Very deep networks like the 164 layers used in Inception-ResNet-V2 yield impressive accuracy, but pale in comparison to frameworks with VGG-16 in terms of speed. Object detection design choices must be made in context depending on whether speed or accuracy takes priority.

3. Multiple spatial scales and aspect ratios

For many applications of object detection, items of interest may appear in a wide range of sizes and aspect ratios. Practitioners leverage several techniques to ensure detection algorithms are able to capture objects at multiple scales and views.

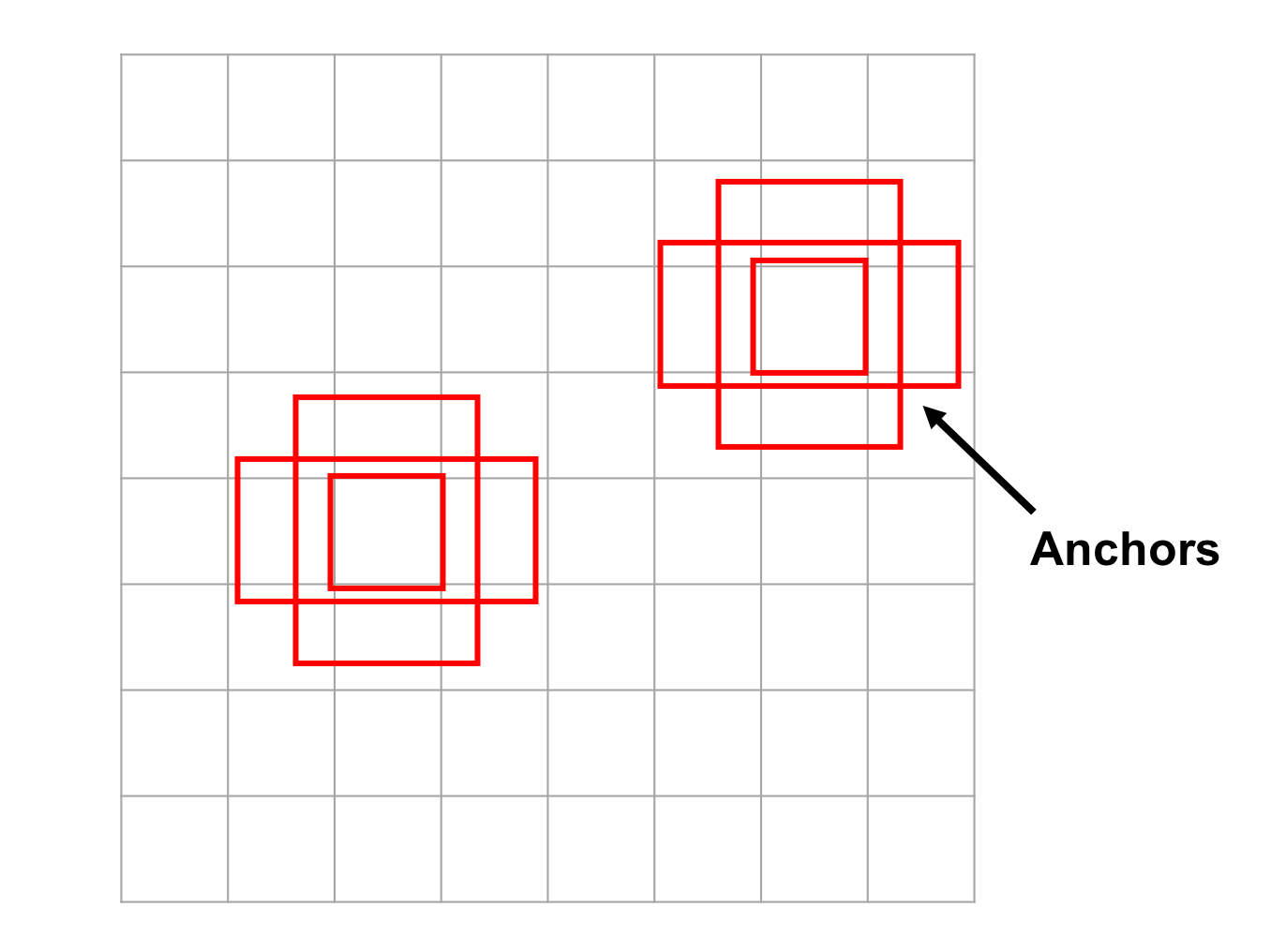

Anchor boxes

Instead of selective search, Faster R-CNN’s updated region proposal network uses a small sliding window across the image’s convolutional feature map to generate candidate RoIs. Multiple RoIs may be predicted at each position and are described relative to reference anchor boxes. The shapes and sizes of these anchor boxes are carefully chosen to span a range of different scales and aspect ratios. This allows various types of objects to be detected with the hopes that the bounding box coordinates need not be adjusted much during the localization task. Other frameworks, including single-shot detectors, also adopt anchor boxes to initialize regions of interest.

Carefully chosen anchor boxes of varying sizes and aspect ratios help create diverse regions of interest.

Multiple feature maps

Single-shot detectors must place special emphasis on the issue of multiple scales because they detect objects with a single pass through the CNN framework. If objects are detected from the final CNN layers alone, only large items will be found as smaller items may lose too much signal during downsampling in the pooling layers. To address this problem, single-shot detectors typically look for objects within multiple CNN layers including earlier layers where higher resolution remains. Despite the precaution of using multiple feature maps, single-shot detectors notoriously struggle to detect small objects, especially those in tight groupings like a flock of birds.

Feature maps from multiple CNN layers help predict objects at multiple scales.

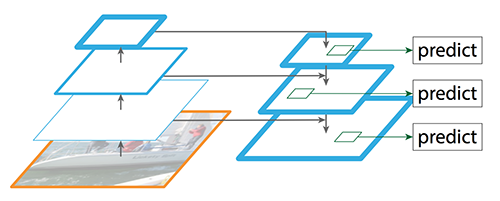

Feature pyramid network

The feature pyramid network (FPN) takes the concept of multiple feature maps one step further. Images first pass through the typical CNN pathway, yielding semantically rich final layers. Then to regain better resolution, FPN creates a top-down pathway by upsampling this feature map. While the top-down pathway helps detect objects of varying sizes, spatial positions may be skewed. Lateral connections are added between the original feature maps and the corresponding reconstructed layers to improve object localization. FPN currently provides one of the leading ways to detect objects at multiple scales, and YOLO was augmented with this technique in its 3rd version.

The feature pyramid network detects objects of varying sizes by reconstructing high resolution layers from layers with greater semantic strength.

4. Limited data

The limited amount of annotated data currently available for object detection proves to be another substantial hurdle. Object detection datasets typically contain ground truth examples for about a dozen to a hundred classes of objects, while image classification datasets can include upwards of 100,000 classes. Furthermore, crowd sourcing often produces image classification tags for free (for example, by parsing the text of user-provided photo captions). Gathering ground truth labels along with accurate bounding boxes for object detection, however, remains incredibly tedious work.

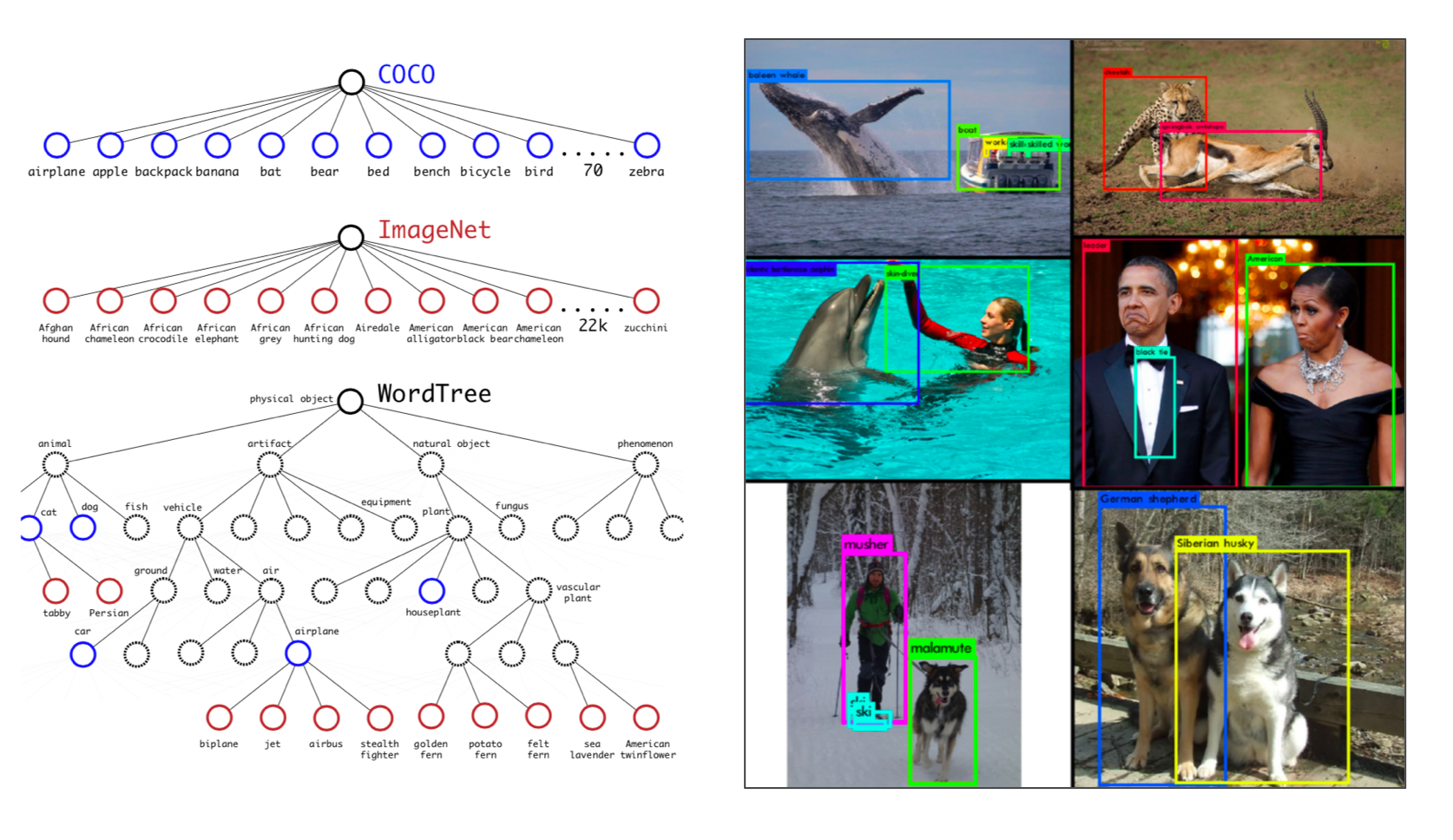

The COCO dataset, provided by Microsoft, currently leads as some of the best object detection data available. COCO contains 300,000 segmented images with 80 different categories of objects with very precise location labels. Each image contains about 7 objects on average, and items appear at very broad scales. As helpful as this dataset is, object types outside of these 80 select classes will not be recognized if training solely on COCO.

A very interesting approach to alleviate data scarcity comes from YOLO9000, the second version of YOLO. YOLO9000 incorporates many important updates into YOLO, but it also aims to narrow the dataset gap between object detection and image classification. YOLO9000 trains simultaneously on both COCO and ImageNet, an image classification dataset with tens of thousands of object classes. COCO information helps precisely locate objects, while ImageNet increases YOLO’s classification “vocabulary.” A hierarchical WordTree allows YOLO9000 to first detect an object’s concept (such as “animal/dog”) and to then drill down into specifics (such as “Siberian husky”). This approach appears to work well for concepts known to COCO like animals but performs poorly on less prevalent concepts since RoI suggestion comes solely from the training with COCO.

YOLO9000 trains on both COCO and ImageNet to increase classification "vocabulary."

5. Class imbalance

Class imbalance proves to be an issue for most classification problems, and object detection is no exception. Consider a typical photograph. More likely than not, the photograph contains a few main objects and the remainder of the image is filled with background. Recall that selective search in R-CNN produces 2,000 candidate RoIs per image–just imagine how many of these regions do not contain objects and are considered negatives!

A recent approach called focal loss is implemented in RetinaNet and helps diminish the impact of class imbalance. In the optimization loss function, focal loss replaces the traditional log loss when penalizing misclassifications: \[ FL(p_u) = -\overbrace{(1-p_u)^\gamma\;}^{*} \log(p_u)\] where \(p_u \) is the predicted class probability for the true class and \(\gamma > 0\). The additional factor (*) reduces loss for well-classified examples with high probabilities, and the overall effect de-emphasizes classes with many examples that the model knows well, such as the background class. Objects of interest occupying minority classes, therefore, receive more significance and see improved accuracy.

Conclusion

Object detection is customarily considered to be much harder than image classification, particularly because of these five challenges: dual priorities, speed, multiple scales, limited data, and class imbalance. Researchers have dedicated much effort to overcome these difficulties, yielding oftentimes amazing results; however, significant challenges still persist.

Basically all object detection frameworks continue to struggle with small objects, especially those bunched together with partial occlusions. Real-time detection with top-level classification and localization accuracy remains challenging, and practitioners must often prioritize one or the other when making design decisions. Video tracking may see improvements in the future if some continuity between frames is assumed rather than processing each frame individually. Furthermore, an interesting enhancement that may see more exploration would extend the current two-dimensional bounding boxes into three-dimensional bounding cubes. Even though many object detection obstacles have seen creative solutions, these additional considerations–and plenty more–signal that object detection research is certainly not done!

ALGORITHMS · LITERATURE REVIEWS