Math Puzzles

Down and Up: A Puzzle Illustrated with D3.js

On a recent vacation my husband and I happened upon an entertainment shop that was well stocked with board games, dice, playing cards, etc. We quickly found an item that both of us, absolute nerds that we are, deemed an essential purchase: a book by Boris A. Kordemsky called The Moscow Puzzles: 359 Mathematical Recreations. No, we didn’t spend our entire vacation solving all 359, but we did bring the book home with us and have continued working through them–often over a glass of wine in the evenings.

One particular puzzle recently caught my attention for several reasons. I’ll come back to those reasons in a bit, but for now, the problem is called “Down and Up” and it goes like this:

Suppose you have two pencils pressed together and held vertically. One inch of the pencil on the left, measuring from its lower end, is smeared with paint. The right pencil is held steady while you slide the left pencil down 1 inch, continuing to press the two pencils together. You then move the left pencil back up and return it to its former position, all while keeping the two pencils touching. You continue these actions until you have moved the left pencil down and up 5 times each. Assume the paint does not dry or run out during this process. How many inches of each pencil are smeared with paint after your final movement?

Take a minute to solve this problem before proceeding if you’d like–spoilers ahead!

First Thoughts

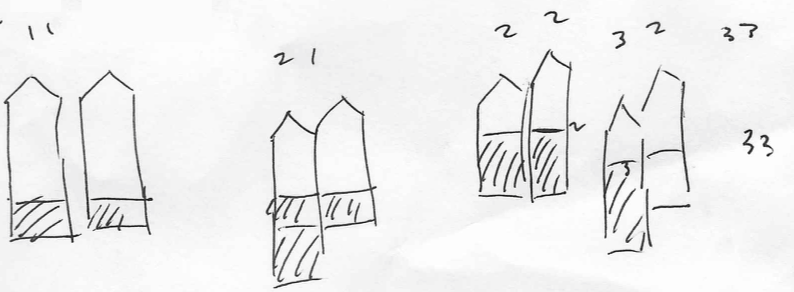

When I first heard this problem, I initially thought that perhaps the paint is not smeared to the right pencil at all and perhaps only one inch of paint appears on the left pencil throughout the entire process. (Did you also expect this?) But the second time I read through the problem I started to visualize what might actually be happening. The solution became much more clear as soon as I tried to make a mental picture of the process. Since my husband was solving the problem with me, I made him this sketch to share what I was thinking:

I managed to distinctly envision the situation, arrive at a solution, and communicate my thought process just with this simple sketch. For many math puzzles a rough picture provides all you need find the answer, but if my crude drawing hasn’t fully conveyed the solution to you, no worries. Let’s dive in a bit more methodically with a much nicer illustration.

Problem Setup

From the problem directions, we know that initially only the left pencil is smeared with paint. Recall though that the left pencil presses directly against the right. This means paint immediately transfers to the right pencil as they are squeezed together. So both pencils are smeared with one inch of paint even before any of the five down-up movements occur.

Solving and Illustrating the Full Problem

The problem gets a little more complicated as the left pencil moves down and up, but returning to a visual interpretation once again helps immensely. Also feel free to reread the problem statement at any point to regain your bearings.

Both pencils are currently smeared with one inch of paint. Then the left pencil moves down one inch while both pencils continue pressing together. Can you envision what happens when the left pencil moves down? Yes! A clean portion of the left pencil makes contact with the bottom of the right pencil; therefore, another inch of paint transfers over to the left.

The left pencil now lingers one inch lower than the right. One inch of the right pencil is smeared with paint, but paint covers two inches of the left pencil. The left pencil moves up in the next step of the problem, coming back to its original position. So the two pencils realign, but what happens to the paint? Since the left pencil continually makes contact with the right, paint smears over to the right pencil and coats two inches of both pencils at the end of the first down-and-up cycle.

The four remaining cycles proceed similarly, with paint transferring first to the left pencil and then to the right. Finally after five rounds of movements, both pencils are smeared with a total of six inches of paint: an initial inch plus five more inches, one for each of the down-up cycles.

This problem ultimately hinges on the ability to translate the problem statement into an explanatory visual. To further contextualize this solution, I created an interactive figure with D3.js. Below both pencils start with one inch of paint as described in the problem setup. Use the “Move Pencil” button to convince yourself of the answer I provided.

Note: these pencils are six fictitious inches long. After the fifth movement, the pencils reach equilibrium in that paint completely covers them. Hit the “Reset” button at any time to start over.

Backstory and Problem Extensions

Earlier I mentioned this problem caught my eye for several reasons. The first reason is exactly what we have been discussing. I marveled at how tricky the problem sounds initially as opposed to how simple it becomes as soon as you construct an appropriate mental image of the situation.

The second reason this puzzle piqued my interest is its history. As explained in Kordemsky’s book, Leonid Mikhailovich Rybakov, a Soviet mathematician who lived in the early 20th Century, created this “Down and Up” problem. I deeply appreciate math problems that pervade through many time periods and geographies. Solving such puzzles allows me to feel more connected to the past and to other mathematicians around the globe.

Finally, this problem sparked my curiosity because Rybakov first thought it up when returning home from a successful duck hunt. Kordemsky encourages readers to contemplate why this could be the case but goes on to explain in his “Answers” section. From The Moscow Puzzles book:

Looking at his boots, Leonid Mikhailovich noticed that their entire lengths were muddied where they usually rub each other while he walks.

“How puzzling,” he thought, “I didn’t walk in any deep mud, yet my boots are muddied up to the knees.”

Now you understand the origin of the puzzle.

Just as the paint smeared the entire length of both pencils, Rybakov’s boots were covered from tip to top because mud had transferred from one boot to the other as he walked.

I continued to think about how this concept might apply to other situations, and I came up with one amusing but slightly unpleasant example. Consider two lines of contra dancers in which the first dancer in the first line unfortunately feels unwell. If this dancer’s sickness is highly communicable, she will, of course, pass along her malady to her dance partner who is positioned across from her. Sometimes in contra dancing participants exchange dance partners by shifting the two lines laterally. Regrettably, when this happens the newly infected dancer will pass the disease back across the line, and eventually the entire group of dancers become ill. Try out my widget below to see this application in action.

Conclusion

I hope you have enjoyed this discussion on one of my new favorite math puzzles along with these illustrative D3 visuals. Making a mental image of a math puzzle is not always easy, but it can be invaluable when solving problems like these–especially if you are a visual learner like myself. The next time you feel stuck on an interview question, check to see if sketching or imagining the physical setup of the problem helps. For me it often does.

I also hope you have enjoyed learning a little about the backstory behind this puzzle. Some of the world’s best math puzzles were created long ago, so I believe looking to the past when attempting to sharpen our minds benefits us greatly. Furthermore, expanding this kind of problem to new applications, like I did with the contra dancers, helps solidify core concepts and builds intuition for future brainteasers. It also makes math problems more enjoyable because you relate them to your own life. So now it’s your turn – can you think of any other “Down and Up” scenarios?

| Check out my D3 code on GitHub! | Pencils and Paint | Contra Dancers |

VISUALIZATIONS · PUZZLES